Properties of Commodity Markets and Price Variability

The price elasticity to changes in demand increases as the degree of differentiation of the good increases

Published by Manuela Agosta. .

Competitive Markets Range Sticky prices Analysis tools and methodologiesThis article aims to analyze commodity markets, introducing the hypothesis that they can be partially differentiable.

Theoretically, a commodity is defined as such because it is a homogeneous good with zero differentiation. Other goods, which have a significantly higher degree of differentiation than zero, are defined as differentiable. However, this duality might lead to a loss of information about goods that have a low but not zero degree of differentiation. From a practical standpoint, these goods with a low degree of differentiation are also referred to as commodities, as they are considered more similar to the theoretical concept of a commodity than to that of a differentiated good.

Analyzing markets defined in economic literature as "commodity markets" and "differentiated goods markets" can be useful for identifying the characteristics of commodity markets when they are partially differentiable.

Commodity Goods: Perfect Competition Market

A good is defined as a commodity when the units produced are identical regardless of the producer selling them in the market.

For example, the production of copper cathodes follows standardized characteristics regarding shape and quality of the copper; thus, any company that meets these characteristics will produce an identical product. Consequently, the price of copper cathodes at a given time and in a given region is the same for all cathodes offered in that market, regardless of the producer.

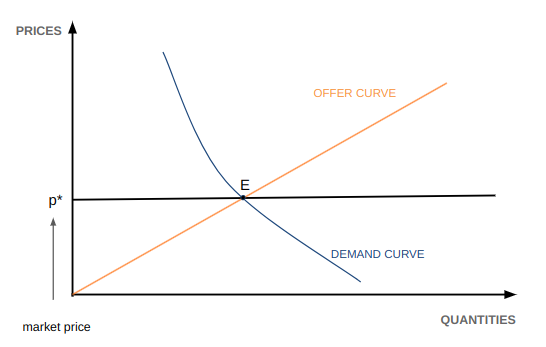

Producers operating in the commodity sector are often referred to as price-taker firms, as no producer has control over the price of their output. The equilibrium price in this case depends on the intersection of market supply and demand, and the price established is exogenous. For example, the production share of the largest grain farming company compared to all globally traded grain is infinitesimal, and even the largest producer cannot influence its price.

Economic literature defines this type of market as perfectly competitive markets.

To understand why a single price is established in a perfectly competitive market, it is useful to first analyze the demand and supply curves for a single firm and then the demand and supply curves for the entire set of firms operating in the market.

Demand and Supply Curves for a Single Representative Firm

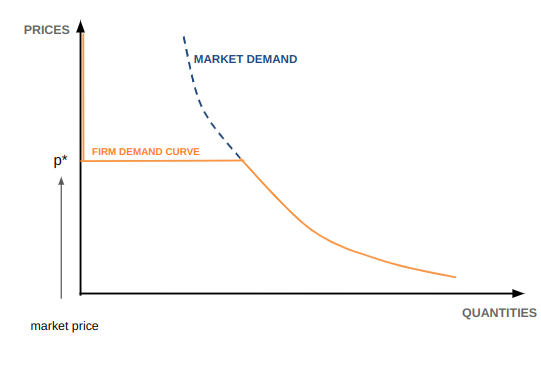

The demand curve for firm i has the following characteristics:

- It is zero when the firm’s price is above the market price p*;

- It is horizontal at the uniform price level p*;

- It coincides with the entire market demand when the firm's price is below the market price p*.

If the firm offers its goods at a price higher than the market price, no customer will buy the product, as they can find an identical (or very similar) one at a lower price. In this case, the firm is forced to exit the market.

Conversely, if the firm sets a price lower than the market price p*, all buyers will prefer to purchase at the lower price and the firm will capture the entire demand. However, this situation is not stable, as each firm will try to adopt the same strategy until the price equals the marginal cost of production. The equilibrium in a competitive market is reached when there is no incentive to enter or exit the market and the market price p* equals the marginal cost of firm i.

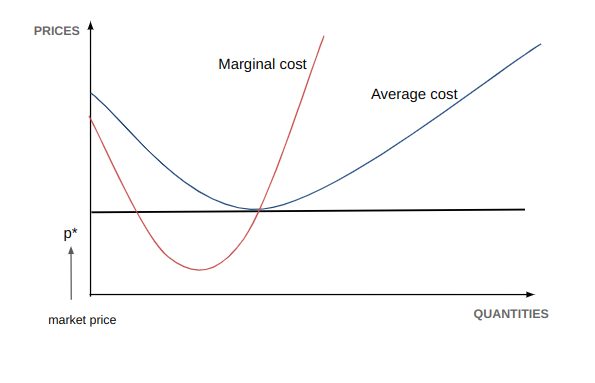

In the two graphs below, on the left is shown the firm's demand curve, while on the right is the firm's supply curve. The latter coincides, in the short term, with the marginal cost curve. In the short term, the optimal choice for a firm is to offer the quantity where marginal costs coincide with the market price[1]. This does not represent, however, a long-term equilibrium, which will be reached when the market price, marginal costs, and average costs coincide, due to the entry and exit of firms.

Demand and Supply of a Single Representative Firm in a Perfectly Competitive Market

| Figure 1: Demand Curve | Figure 2: Supply Curve |

|

|

Aggregate Demand and Supply Curves

Aggregating the demand and supply curves of individual firms results in the aggregate demand curve and the aggregate supply curve, shown in the following graph:

Figure 3: Short-Term Aggregate Demand and Supply in a Perfectly Competitive Market

The supply curve shown in this graph represents a short-term situation, where changes in demand reflect changes in the supply of individual firms. Price changes move along the marginal cost curve, assumed to be identical for all firms.

Do you want to stay up-to-date on commodity market trends?

Sign up for PricePedia newsletter: it's free!

Differentiated Goods: Monopolistic Competition Market

A good produced by a firm is considered differentiated when it has unique characteristics compared to the products of other firms. In this context, firms compete not only on price but also on the distinctive features of the good. If a product is preferred over competitors’ products, higher prices can be set. For example, a buyer of mechanical components might accept a higher price if the supplier offers superior quality (such as lower tolerances, better packaging, superior logistics services, etc.) compared to others.

This market power that some firms can exercise has led economists to coin the term "monopolistic competition" (E. Chamberlin) to describe this type of market. This oxymoron highlights the fact that, while there are several firms in competition with each other, each holds a certain amount of monopolistic power in determining market conditions.

The monopolistic competition market is positioned midway between perfect competition and monopoly. It shares the following elements with the former:

- Presence of numerous and small firms in the market, none of which has significant control;

- Freedom of entry and exit: a firm enters the market when it believes it can sell a similar but distinctive product compared to competitors; conversely, it exits when it fails to sufficiently differentiate itself.

The characteristics shared by monopolistic competition with monopoly include:

- Product differentiation: the greater the differentiation of a product, the less its substitutability and the greater the market power of firms;

- Imperfect knowledge: unlike in a competitive market, where the price is unique and known to everyone, in a monopolistic competition market firms do not know the pricing strategies of competitors, so knowledge is imperfect;

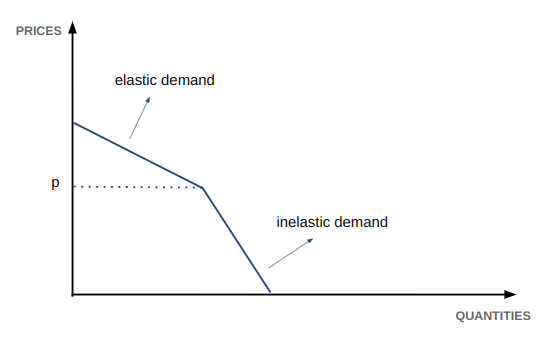

- The demand curve for the individual firm is negatively sloped and inelastic up to a certain price level, then becomes more elastic.

The shape of the demand curve for the individual firm reflects the substitutability of the product: the more substitutable a product is, the flatter (more elastic) the demand curve will be. In the extreme case, there is perfect competition, with a perfectly elastic demand curve, as shown in Figure 1. Conversely, the more differentiated and less substitutable a product is, the greater the firm's power to raise the price without losing demand shares.

The firm is interested in raising prices as long as the demand curve is inelastic, as demand decreases only slightly with increasing prices. However, when demand becomes elastic, price increases cause a significant reduction in quantity sold, so the firm stops raising prices.

This situation can be represented with a kinked demand curve:

Figure 4: Demand Curve for a Firm in Monopolistic Competition

Effect of Different Markets on Price Variability

The distinction between a perfectly competitive market and a monopolistic competition market is particularly useful for analyzing the price dynamics of commodities. This distinction allows us to hypothesize how prices vary in response to changes in demand. In a perfectly competitive market, the supply curve tends to be more elastic with respect to prices compared to a monopolistic competition market. This leads to greater price elasticity with respect to demand changes[2]. Consequently, commodity prices are more or less variable depending on the degree of differentiation that producers can introduce in their offer: the greater the differentiation, the lower the price variability, while a good that is a commodity (and thus less differentiable) shows greater price variability with respect to demand changes.

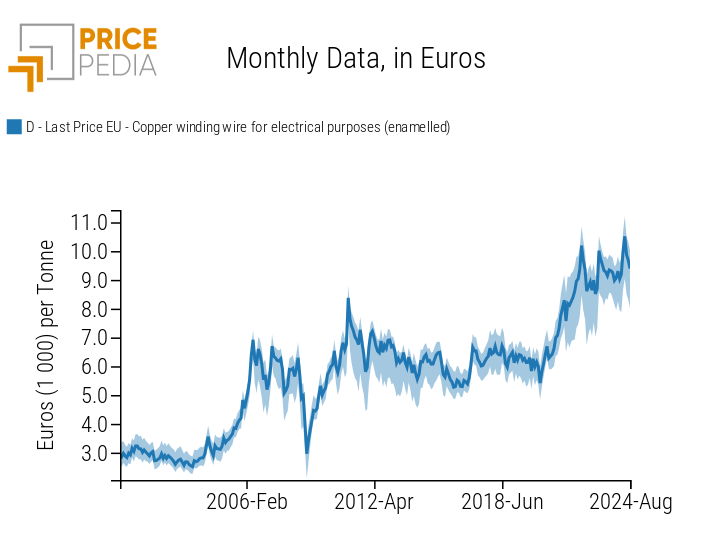

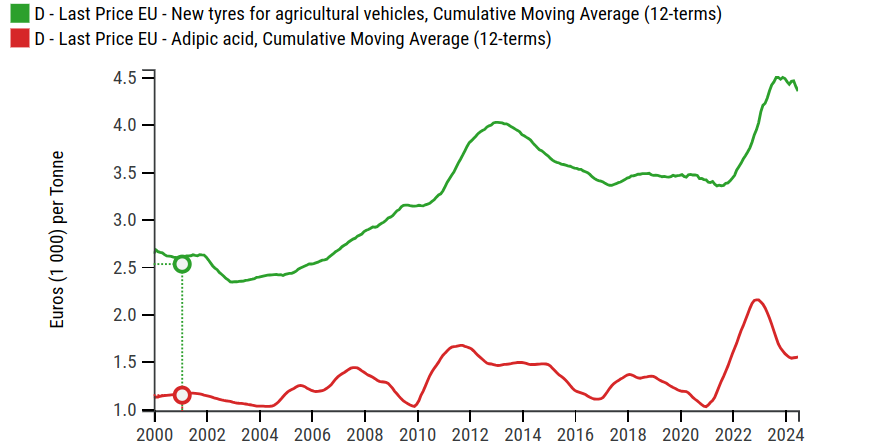

Analytically, price elasticity with respect to demand is the primary tool for evaluating this dynamic. One method to determine whether this elasticity is high or low is to observe historical price series, as illustrated below for the commodities adipic acid and tractor tires:

Figure 5: Price Trends of Adipic Acid and Tractor Tires

It is observed that the price of adipic acid fluctuates much more than the price of new tractor tires. This suggests greater differentiation in the latter case: although still considered commodity goods, their price is less sensitive to changes in demand.

Conclusions

Product differentiation plays a fundamental role in determining production and pricing for firms. In the absence of differentiation, producers have very limited pricing power. In this case, prices are mainly determined by market conditions, i.e., supply and demand, rather than the distinctive characteristics of the product. Conversely, more differentiated products can maintain higher prices even when, in other markets, a decrease in demand leads to a reduction in prices. An important measure of the degree of differentiation in commodities is the price elasticity with respect to demand, which represents the percentage change in price in response to a percentage change in demand: the greater this elasticity, the greater the homogeneity of the product.

[1] If the market price is above marginal costs, the firm has an incentive to increase production until marginal costs equal the market price. Conversely, if marginal costs are above the market price, the firm reduces the quantity supplied.

[2] For an analysis of how the slope of the supply curve affects price elasticity with respect to demand, see Sulfur and Sulfuric Acid: Price Elasticity of Demand.