The price transmission mechanism: how much does market structure matter?

Market structure is relevant in explaining how increases in production costs result in increases in the final price

Published by Manuela Agosta. .

Strumenti Competitive Markets Copper Range Sticky prices Analysis tools and methodologies

In recent years, the number of raw material prices listed on official exchanges has increased. The availability of this information is becoming more accessible, offering a purchasing department the ability to improve its understanding of the price evolution of purchased goods, especially if these are first-stage transformations of raw materials.

This knowledge is based on two fundamental aspects: the first concerns the impact that the raw material has on the price of the purchased good; the second aspect is the speed with which price changes in the raw material are reflected in the price changes of the final product. The first understanding can be deepened by using the should cost approach [1]. The second, the specific subject of this article, requires an analysis of the degree of differentiation of the purchased product and the type of market in which it is traded, whether it is perfectly competitive or monopolistic.

The first section of the article conducts an exploratory analysis in microeconomic terms, while the second part empirically verifies the findings through a comparison between two commodities that use copper in their production process.

Perfect Competition Market

It can be shown, starting from a graphical observation, that price transmission in a competitive market is completed in the short term.

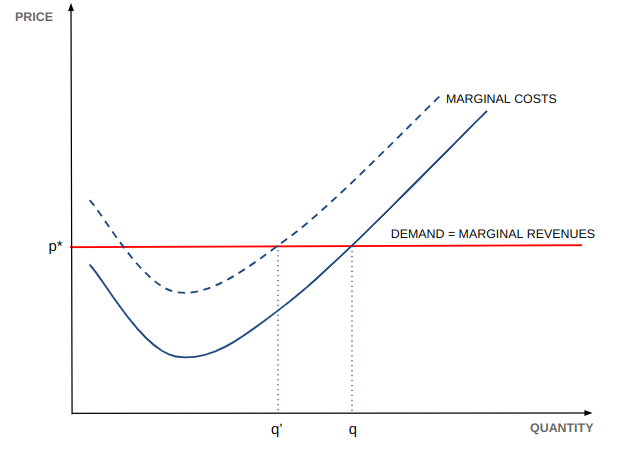

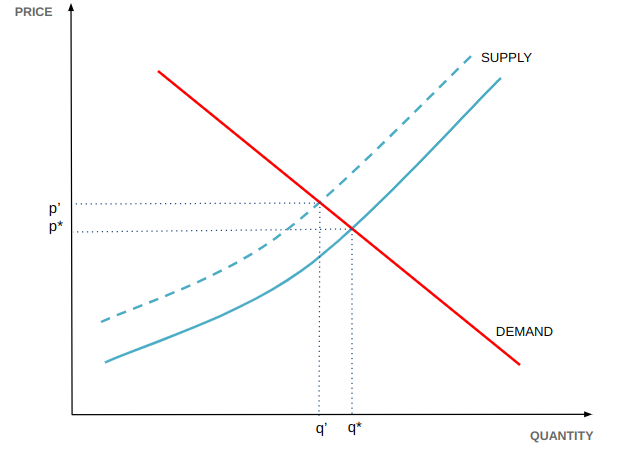

In a perfectly competitive market, firms are price-takers, meaning they accept the market price as given (p*). If the production cost of an input increases for all firms, the overall market supply decreases, and the equilibrium price rises (1.b):

| 1a: Short-term for the individual firm | 1b: Short-term for the market |

|

|

The price transmission mechanism can be explained in the following steps:

- when production costs rise due to the increase in input prices, the individual firm has no significant market share and thus cannot raise its price (1.a): no buyer would purchase an identical product at a higher price (perfectly elastic demand for the firm). Therefore, at the new cost level, marginal cost exceeds marginal revenue, and the firm has an incentive to reduce production.

Since all firms in a competitive market are identical, this leads to a reduction in aggregate supply (1.b); - the reduction in aggregate supply can also be explained by the exit from the market of firms unable to cover the new higher average variable costs, especially in the short term: the exit of such firms reduces aggregate supply;

- the reduction in supply creates an imbalance where the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied, and the excess demand is eliminated by a price increase (from p* to p’): buyers are unwilling to pay the same quantity of output at a higher price, so the quantity demanded decreases until it matches the quantity supplied.

Therefore, in perfect competition, price adjustment is immediate and complete in the short term.

Do you want to stay up-to-date on commodity market trends?

Sign up for PricePedia newsletter: it's free!

Monopolistic Competition Market

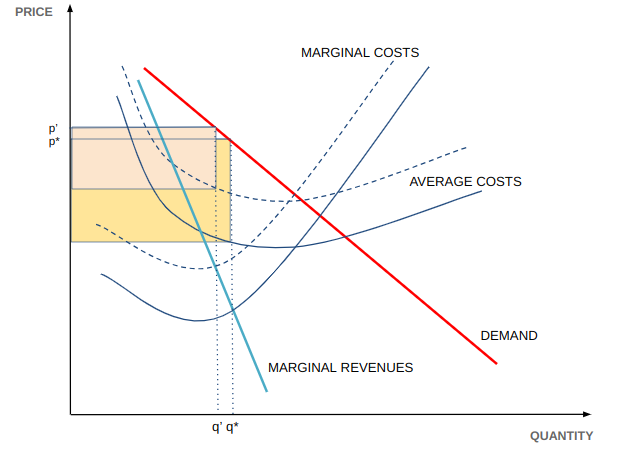

In monopolistic competition, the transmission mechanism from production costs to the final price is not immediate and is completed only in the long term:

- in the short term, the demand curve is relatively inelastic, allowing for extra profits similar to a monopoly: thanks to partial product differentiation, firms have some market power and can set a final price different from their competitors. The magnitude of the price increase depends on the shape of the demand curve, particularly its price elasticity: the more elastic it is, the smaller the final price change.

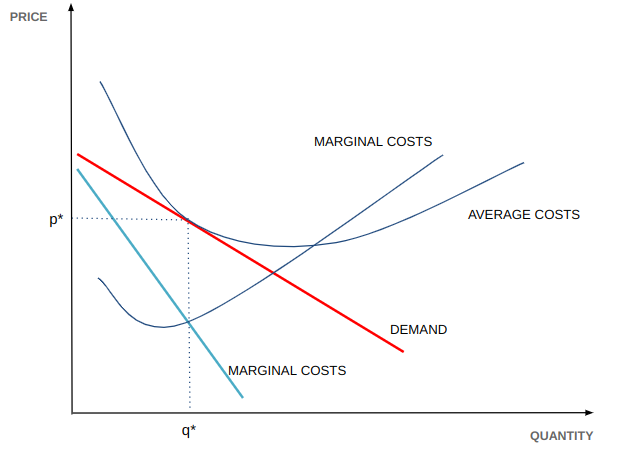

In any case, however, the increase in production costs leads to a price increase and a reduction in profits (from the darker rectangular area to the lighter one); - in the long term, the absence of entry barriers encourages firms that see the possibility of realizing extra profits to enter the market. This process makes the demand curve more elastic relative to price and gradually shifts it to the left, until it becomes tangent to the average cost curve. In this situation, long-term equilibrium is reached, where economic profits are zero for all firms, as in a perfectly competitive market (2.b).

| 2a: Short-term for the individual firm | 2b: Long-term for the individual firm |

|

|

The reason why the price adjustment process in response to rising production costs is not immediate is that, in the short term, the firm decides to reduce profits rather than lose significant demand shares (downward-sloping demand curve); in the long term, due to the increased production costs and the fact that extra profits are now zero, some firms exit the market, reducing aggregate supply and pushing prices up, similar to what happens in perfect competition.

Empirical Evidence

To empirically verify the theory presented so far, two materials are examined:

- refined copper wires with a maximum cross-section greater than 6 mm (non-insulated);

- copper electrical wires for winding, for electricity, enameled or lacquered (insulated);

The copper electrical wires for winding have a higher degree of differentiation, as they undergo insulation processes to prevent short circuits in the windings. The insulation is typically made of enamel, lacquer, or other insulating materials (PVT, Teflon, etc.), allowing producers to differentiate their products slightly, gaining limited market power.

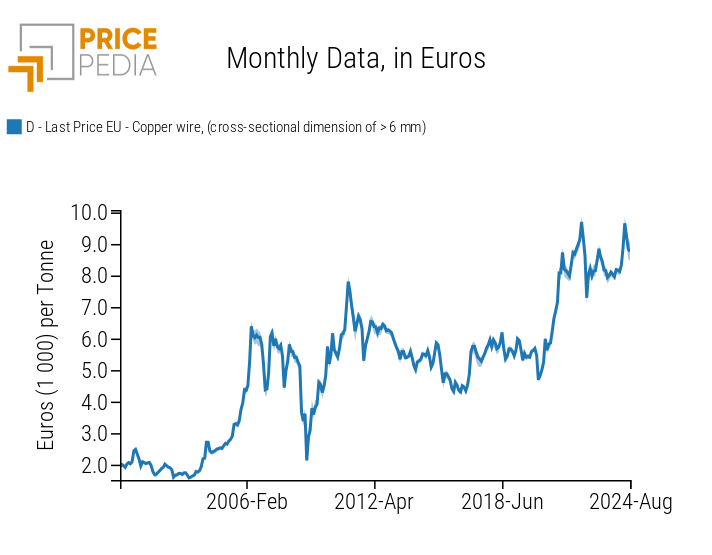

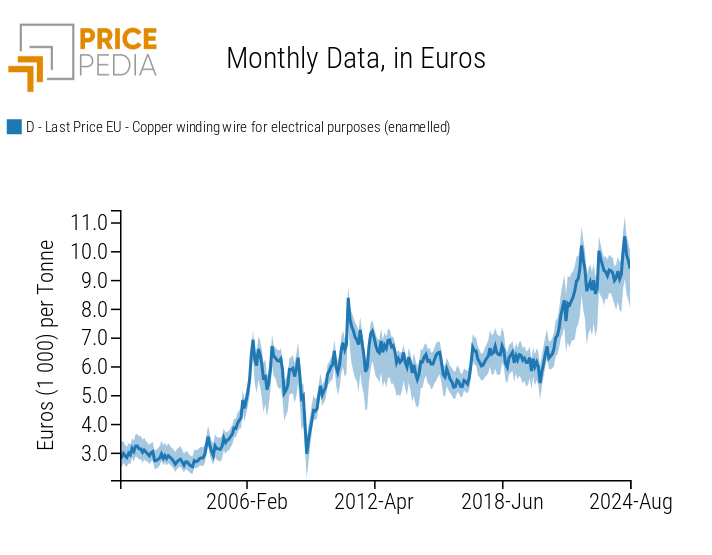

Indeed, by comparing the price dispersion of the two commodities' historical data, it can be observed that non-insulated electrical wires have low (almost negligible) price dispersion, while insulated electrical wires show greater dispersion due to different prices among firms in the market:

| Non-insulated copper electrical wires | Insulated copper electrical wires |

|

|

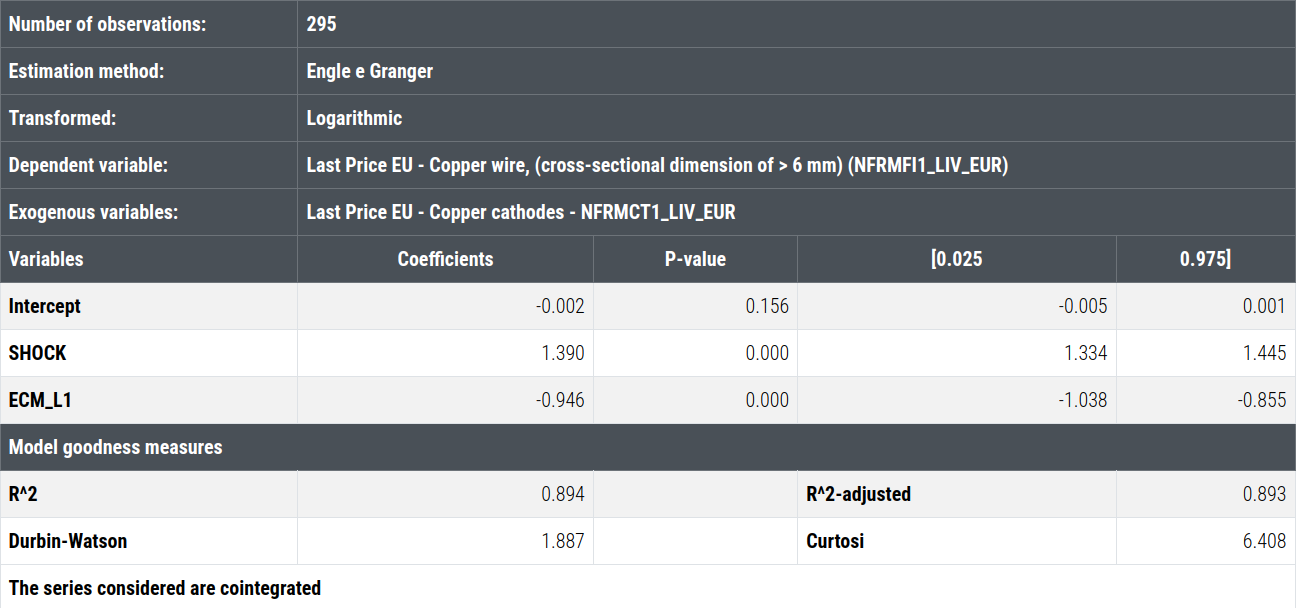

Econometric Approach: The Case of Non-insulated Copper Wires

In the following analysis, a model is developed to investigate price variations in non-insulated copper electrical wires in response to changes in the production input price of copper.

Based on the previous discussion, since this is a perfectly competitive market, the price variation should be complete and immediate. [2]

Short-term Estimate Results

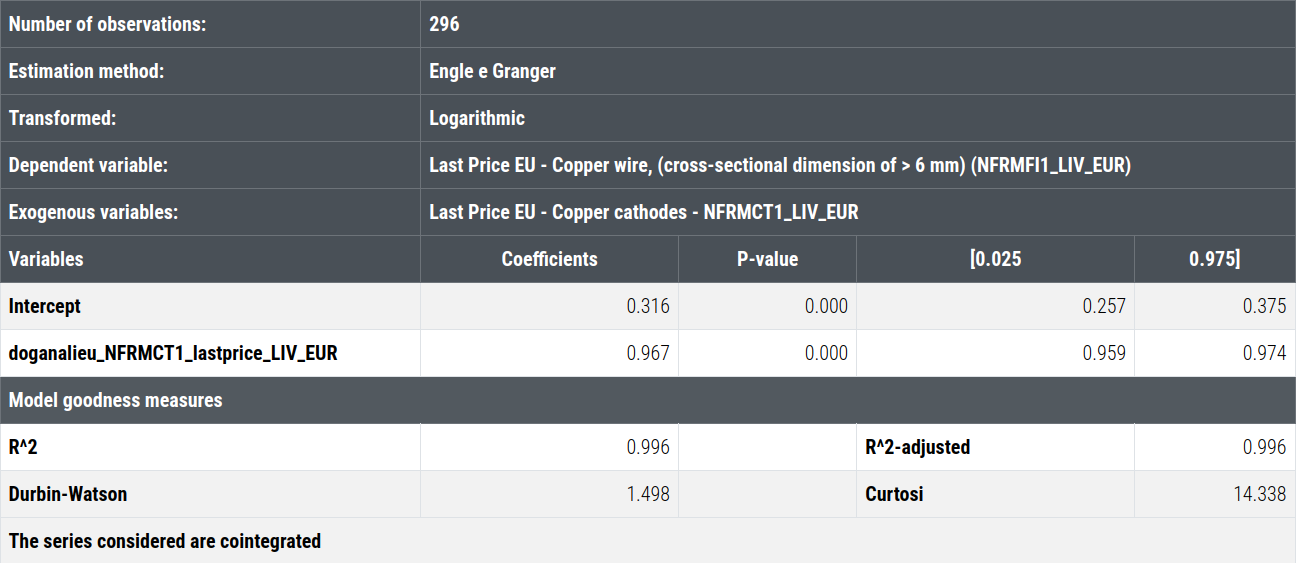

Long-term Estimate Results

Both the short-term and long-term models show a very high R2, indicating a good fit of the model. The long-term coefficient (0.967) is close to 1 and demonstrates that when the price of copper increases by 10%, the price of non-insulated electrical wires increases by 9.67%. This coefficient helps analyze the impact that the price of a certain production input has on the final price of a commodity. In this case, copper is the only material input in the production of copper wires, and the impact is therefore very high.

The other key parameter to consider is the ECM (Error Correction Mechanism), which is -0.946. It indicates that after a shock to production costs, 94.6% of the deviation from the long-term equilibrium prices, which would have been achieved without the shock, is corrected within one period, leaving only a small portion of the deviation to be corrected in subsequent periods. This indicates that price transmission is immediate and complete in the short term, consistent with the theoretical predictions of the perfectly competitive model.

Econometric Approach: The Case of Insulated Copper Wires

In the case of insulated copper electrical wires, we expect price transmission to be slower and less complete than in the previous case, due to the firm's market power derived from product differentiation (see discussion on monopolistic competition).

From the price graphs shown above, insulated copper wires have shown greater price dispersion over time, indicating less perfect price transmission:

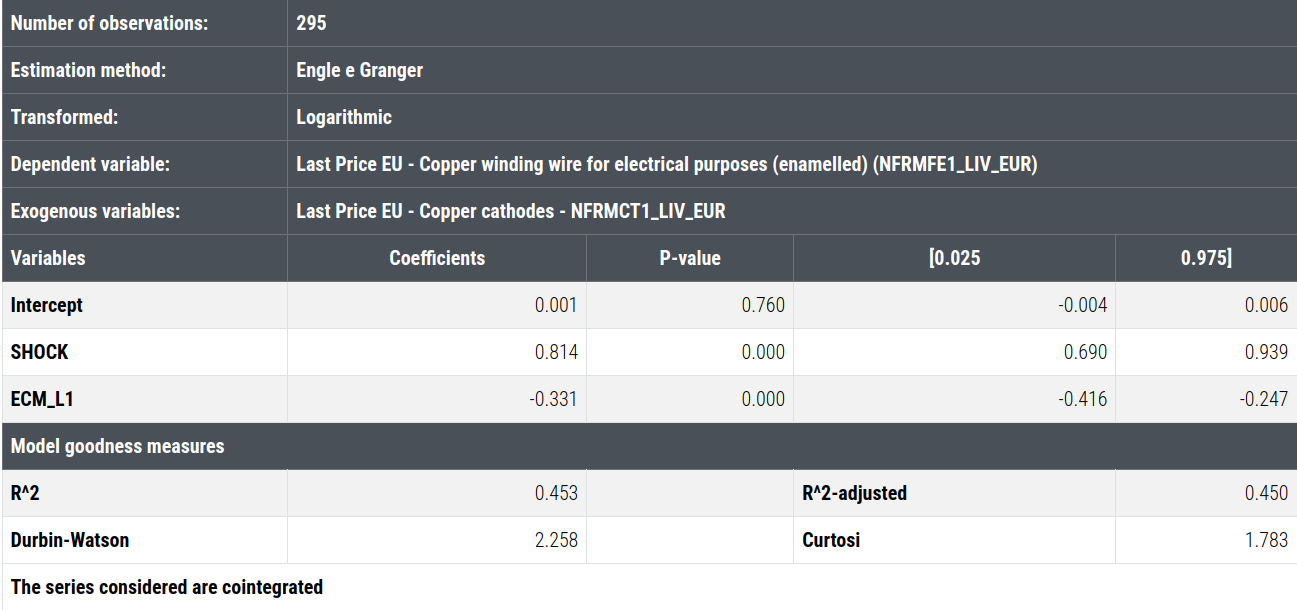

Short-term Estimate Results

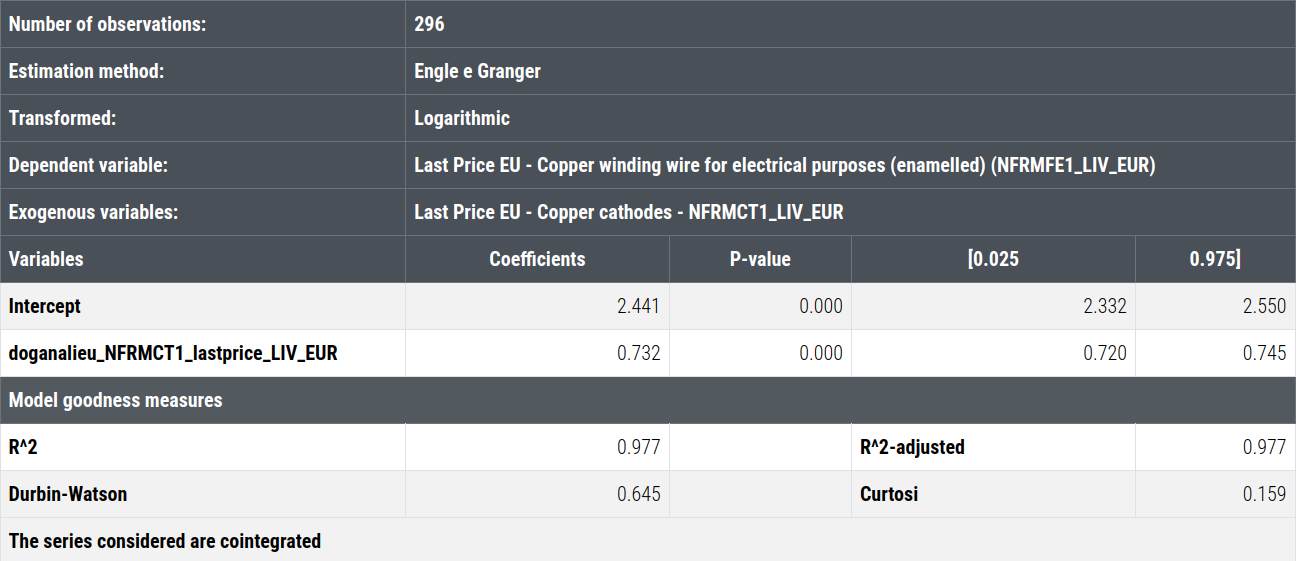

Long-term Estimate Results

In this case as well, the model fits the data well. The long-term coefficient is 0.732: a 10 percentage point variation in the price of copper leads to a corresponding 7.32% variation in the final price of copper electrical wires. In this case, copper is not the only input in production; other materials, such as lacquer or enamel, are used as insulators during the manufacturing process. As a result, the price impact on costs is lower compared to non-insulated copper wires.

In the short term, the ECM parameter is -0.331, indicating that only 33.1% of the deviation from equilibrium is corrected within one period, and full adjustment takes several months, as predicted by microeconomic theory.

Conclusions

A buyer purchasing products derived from a raw material can gain valuable insights from understanding the type of market and the degree of product differentiation. This knowledge can provide indications, for example, about the speed at which financial prices of a raw material, quoted on an official exchange, translate into changes in the market prices of the goods they purchase.

Both theoretical and empirical analyses highlight the existence of transmission mechanisms between changes in input prices and changes in output prices, which vary based on the degree of product differentiation and, consequently, the type of market, whether perfectly competitive or monopolistic, on which the good is traded.

For undifferentiated goods (such as non-insulated copper wires) traded in perfectly competitive markets, the change in the price of an input is reflected immediately in the final price of the product. In contrast, as product differentiation increases, the transmission of input price changes to output price occurs more slowly: for insulated copper wires, which can be considered slightly differentiated, the transmission process takes several months, and for products with a significant level of differentiation, this process may require a period extending beyond a year.

[1] For further information on the should cost approach, see the article Should Cost and Knowledge of Hidden Curves: Two Tools for Negotiation

[2] The Engle and Granger estimation model is used, which assumes that even though the two price series may follow stochastic processes (i.e., vary over time), there exists a linear combination that is stationary (i.e., has constant mean and variance over time), at least in the long term.